The strive for physical and spiritual well-being is a binding force in our alienated society. There are various recipes on how to stay balanced and ‘take care of the self‘, weaving a maze of numerous principles on what is regarded healthy, pure and natural.

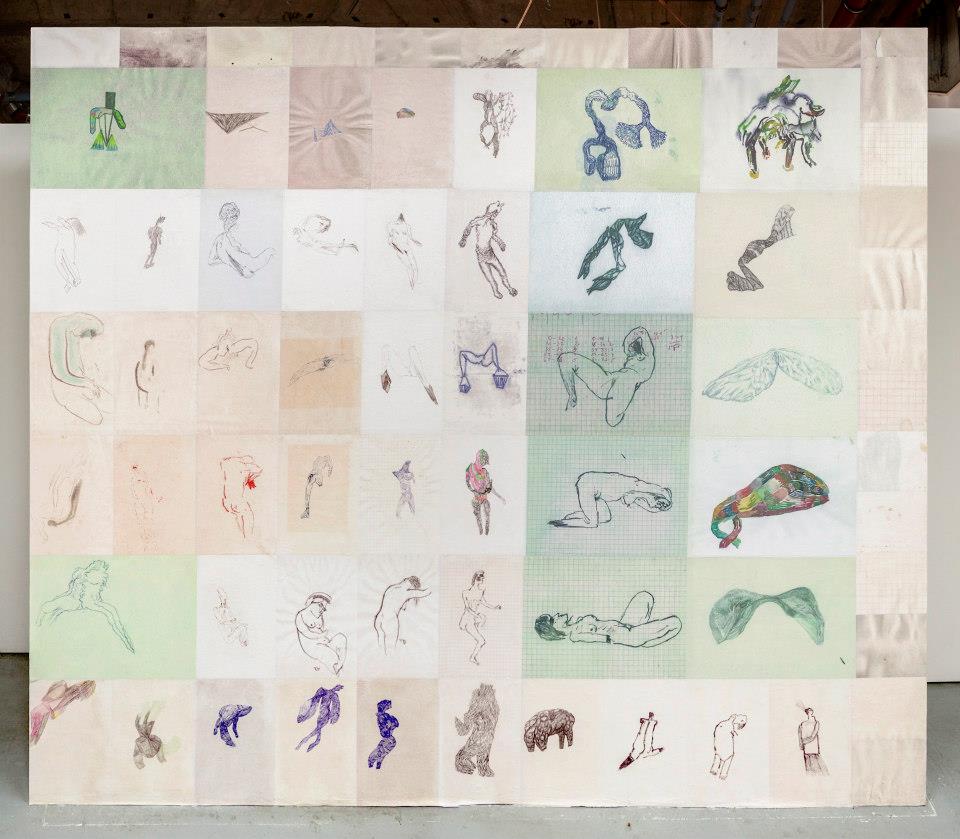

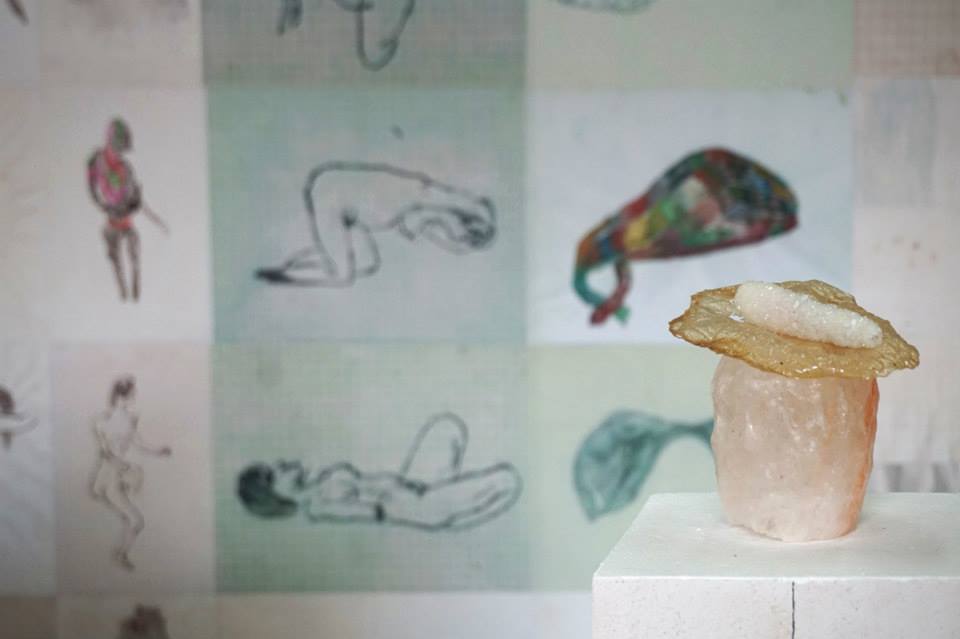

Dominika Trapp’s room installation Dazed and Orthorexic depicts the struggle for self-therapy and stability that are achieved by means of a strict, calculated control over everyday nourishment. While pursuing a quest for self-liberation through asceticism, eating becomes a chore, a continuous, mechanical digestion ofwhat is thought to be ‘right’ and ‘good‘, rather than ‘tasty’ or ‘pleasant’. Trapped in a bubble of paradoxes: What was considered healthy bears a deathly disease, the appetite for purity turns into a paranoid anxiety. The resulting obsession and distorted self-image spreads over the entire environment. The artist is interested in the psychological depth of being under the influence of such nourishment fantasies, turning eating into a performative act. Trapp takes inspiration from her own adolescence life that was overruled by healthy lifestyle theories and her encounters with various controlled diets and purity séances.

Dazed and Orthorexic plunges into the context of female asceticism, through personal experiences as well as historical examples ranging back to the Middle Ages. Furthermore, the exhibition presents references to the key figures of the Hungarian lifestyle reforming movement.

/Krisztina Hunya, curator/

About the paintings:

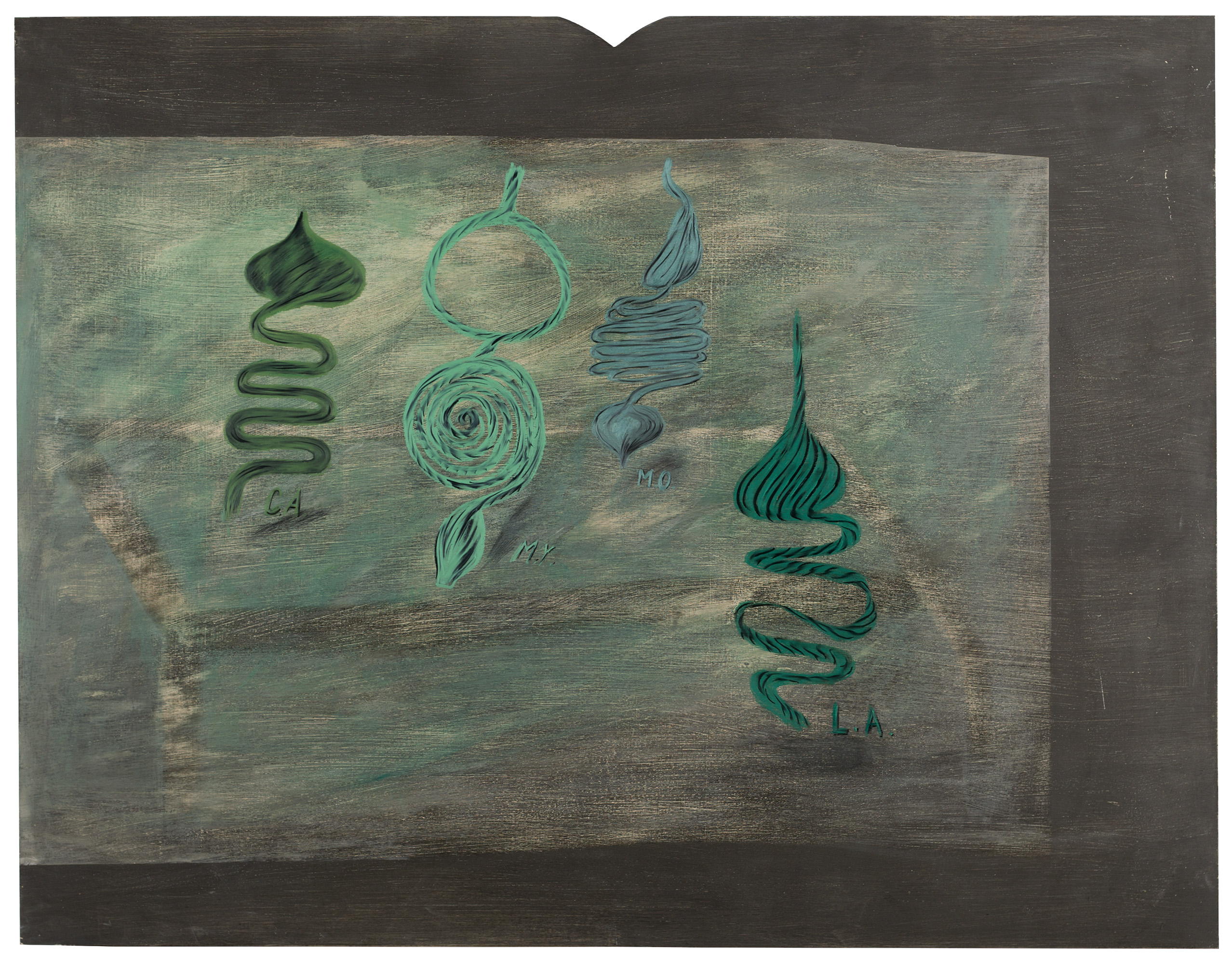

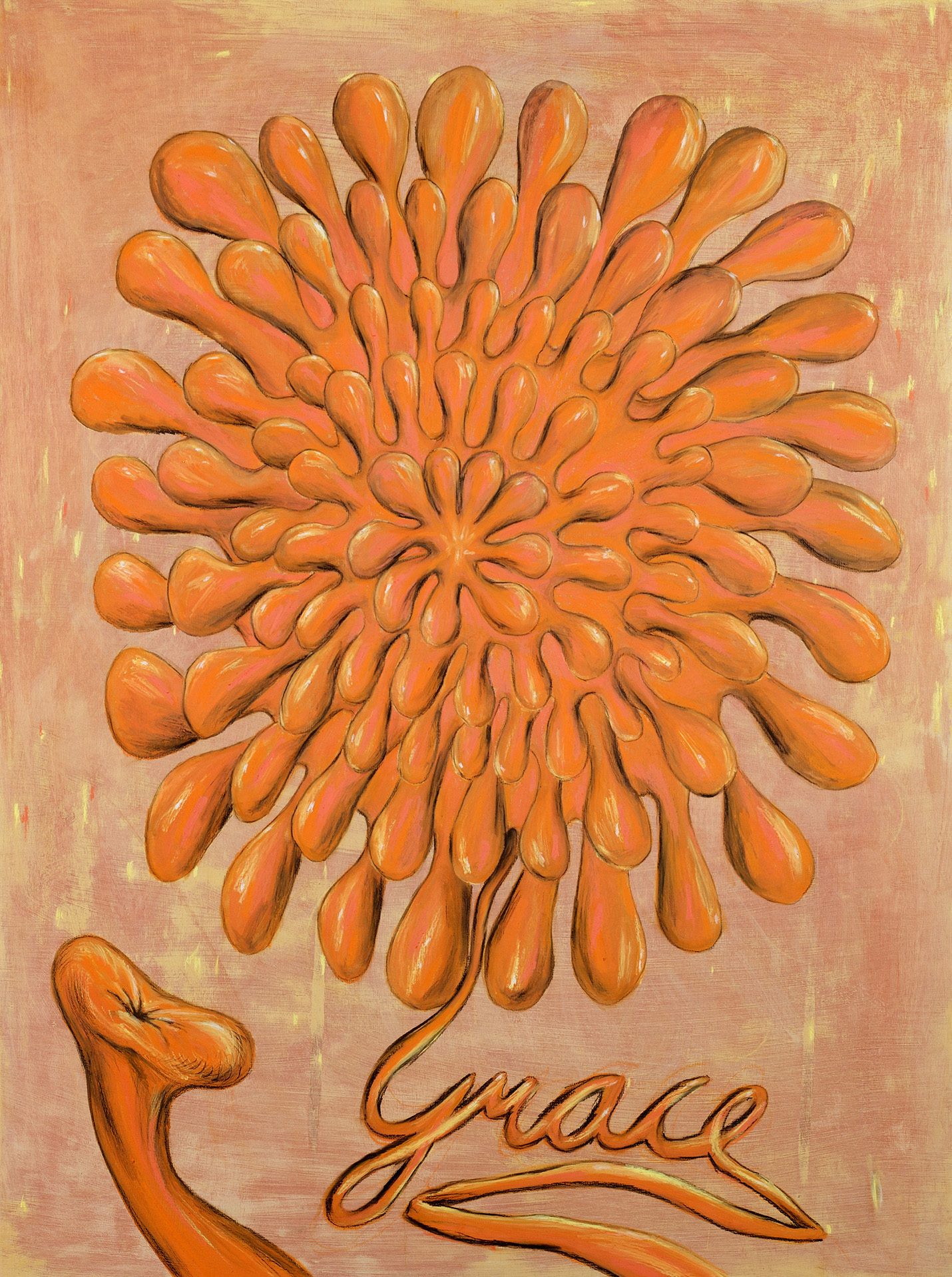

Digestive Tracts of Medieval Female Mystics, 2015, lime casein, natural earth pigments on wood panel

“Medieval mystics especially the historic lay women created identities for themselves by

making literal spectacles of their bodies.”

“They talk of god as food.”

“Just because these women didn’t write their stories they wrote their bodies. The words are male

but the actions are female.”

/Deirdre A. Riley: Late Medieval Women: Ascetic Performance and Subversive Mysticism/

Christina the Astonishing (1150-1224)

At the age of 21 she experienced resurrection and became ascetic. Her diet consisted of garbage

and others’ left-overs. Villagers captured her and kept her starving, she nursed herself for

nine weeks.

Margaret of Ypres, (1216-1237)

She was torturing herself since the age of 7. Her diet was mainly the Eucharist. In her visions she

was feeding on the body of Christ.

Mary of Oignies (1177-1213)

She once ate a bite of meat and she was so disgusted that she cut a piece out of her own flesh

and buried it in the ground.

Lutgard of Aywiéres (1182-1246)

She was chosen by God. Her diet was less extreme, restricted to only beer and bread or bread

and vegetables in 7-year cycles. In her visions she was nursed by Christ, and she was feeding

on the wounds of Christ.

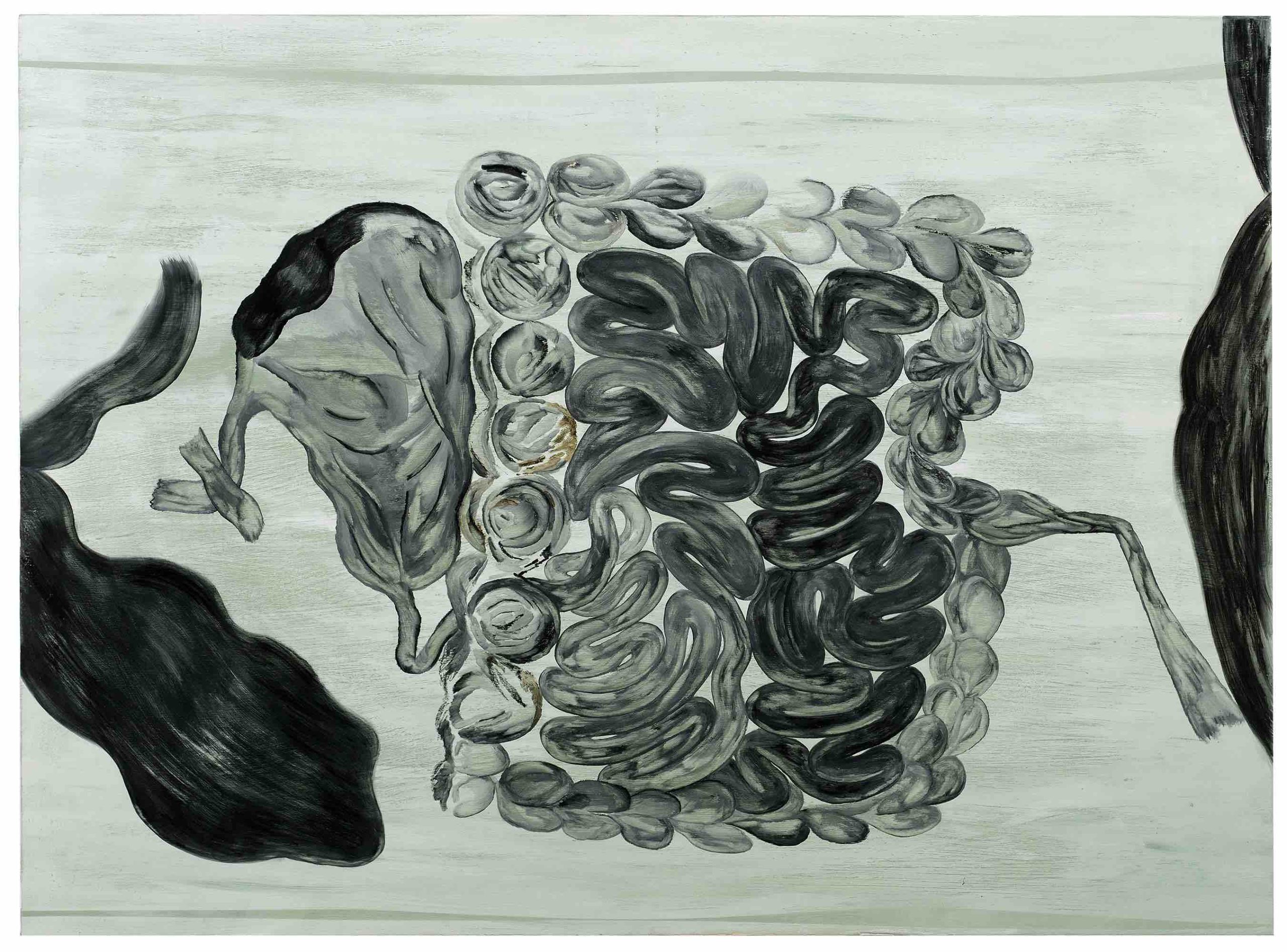

Simone Weil’s Intestines, 2015, lime casein, natural earth pigments on wood panel

“Weil was more a mystic than a theologian. That is, all the things she wrote were field notes

for a project she enacted on herself. She was a performative philosopher.

Her body was material. “The body is a lever for salvation.” – she thought in Gravity and Grace.

“But in what way? What is the

right way to use it?”

/Chris Kraus: Aliens and Anorexia/

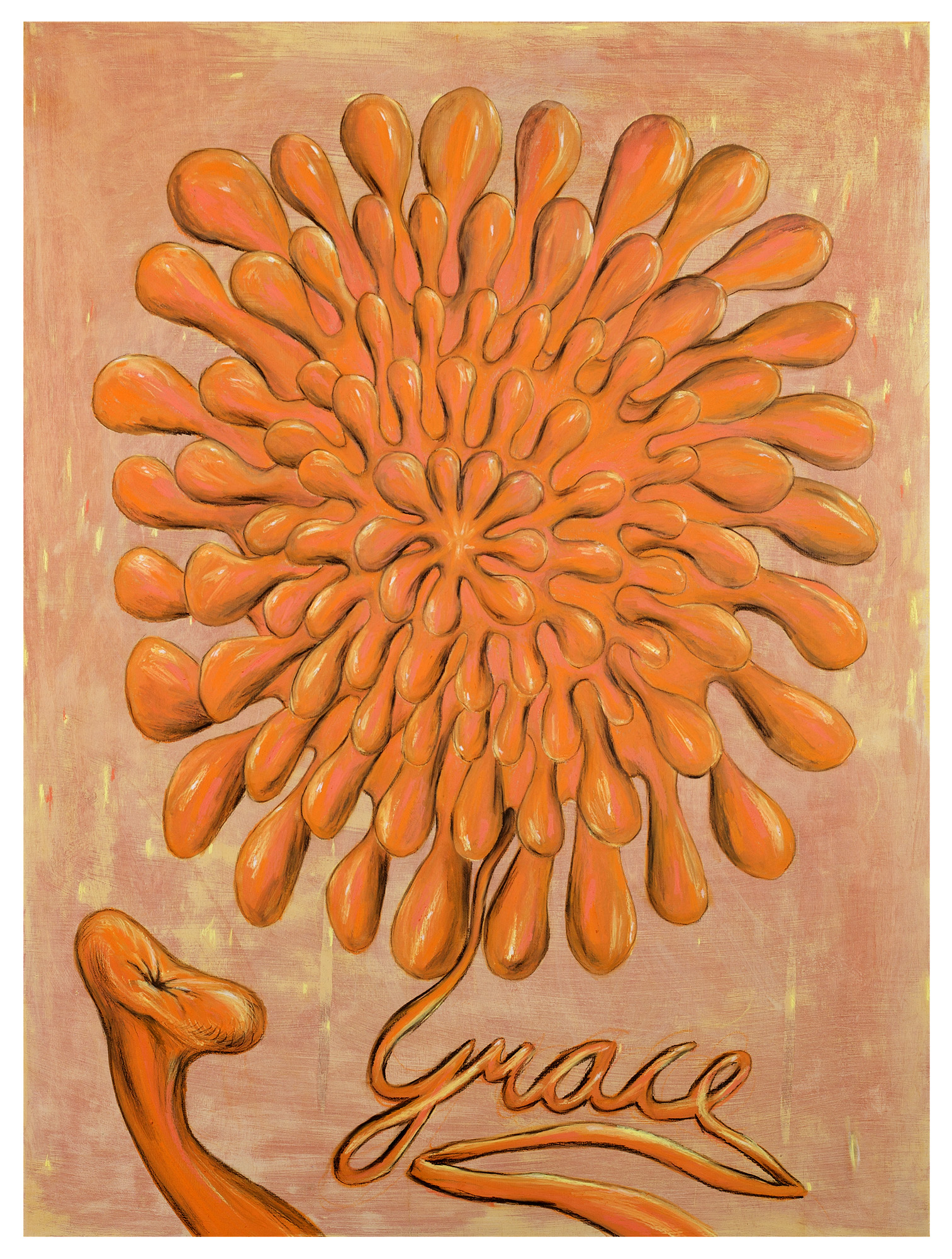

Intestinal Villus of Chris Kraus, 2015, lime casein, mulberry and natural earth pigments on wood panel

“Female acts are always subject to interpretation. We don’t say what we mean.

It’s inconceivable that the female subject might ever simply try to step outside her body,

because the only thing that’s irreducible, still, in female life is gender.”

/Chris Kraus: Aliens & Anorexia, (2000)/

In her writings Chris Kraus often deals with the life of teenage girls, the bodily self-image and

its distortion. In her book Aliens & Anorexia she studied – among others – the life and beliefs

of Simone Weil. Honoring her, Kraus’ film Gravity and Grace bears the same title as Weil’s

seminal work that consists of various passages selected from her notebooks.

Listen to the sound of the exhibition, while reading the text and watching the images below.

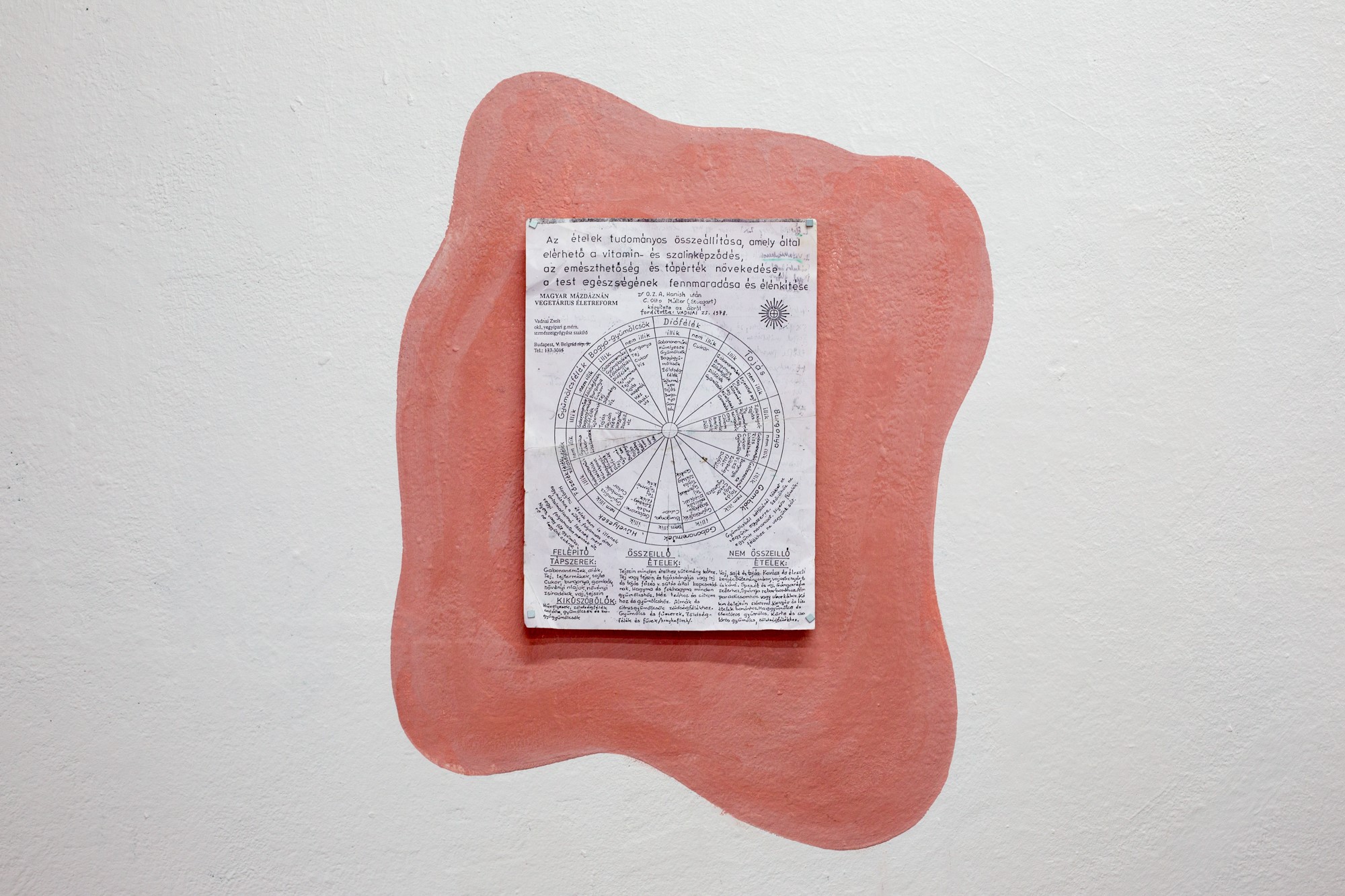

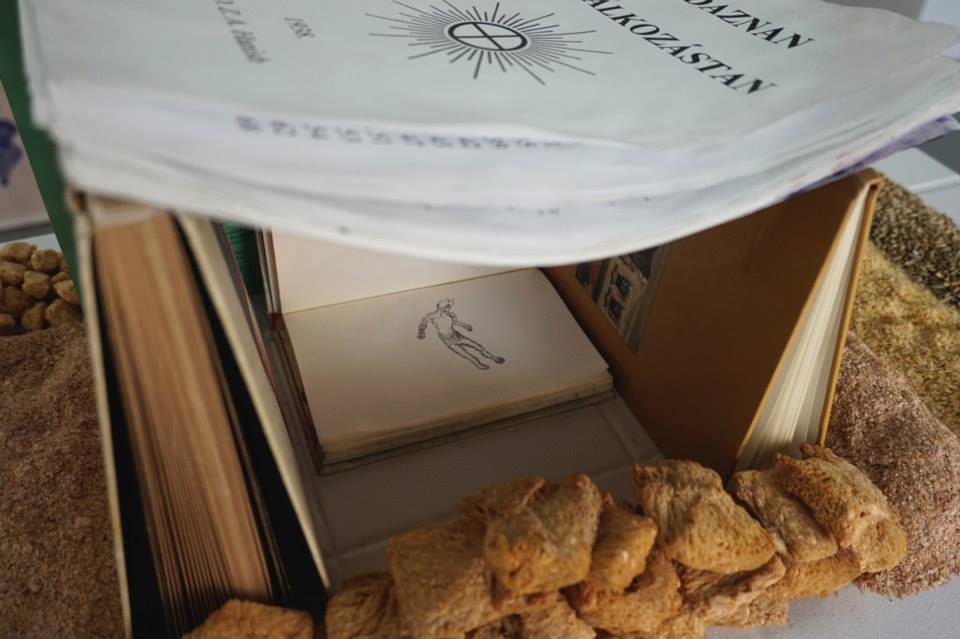

István Ferencsik: Practical Lifestyle Reform – Based on the Science of Mazdaznan (details)